Algal Blooms in the Gulf of America

We’ve built our modern world on a simple idea: if some nutrients are good for crops, more must be better.

But what happens when those nutrients overflow the fields that need them and flood into the waterways that don’t?

Scientists like Dr. Stan Harpole, an ecologist who studies how species coexist, are sounding the alarm. His research shows that excess fertilizers — once hailed as the key to abundance — are quietly erasing biodiversity and disrupting the complex balance that keeps ecosystems alive.

The Paradox of Plenty

In grasslands, plants once competed across a dazzling variety of niches — different strategies for capturing sunlight, nitrogen, phosphorus, water, and space. These overlapping needs allowed dozens of species to coexist.

But as Harpole explains, when we saturate the soil with nutrients, we erase that complexity:

Plants are competing for many, many things simultaneously. As we add nitrogen or phosphorus, we remove those differences — and as we make everything superabundant, the system collapses into a single limiting factor. Suddenly, only the best competitor survives.

In other words, too much of a good thing destroys diversity.

From Fields to Oceans: The Cascade of Nutrient Pollution

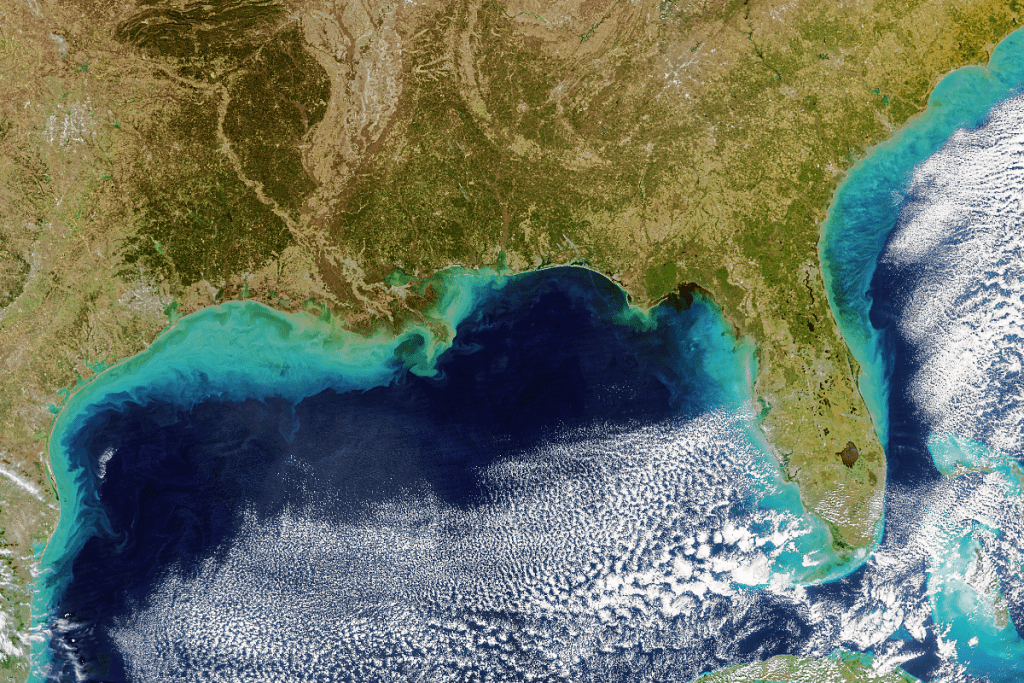

The same pattern plays out on a planetary scale. Fertilizers wash from farm fields into streams and rivers, carrying nitrogen and phosphorus to estuaries, gulfs, and coral reefs. Once there, they feed explosive blooms of algae that block sunlight and choke off oxygen.

The result: vast dead zones where few species can survive. In the Gulf of America, this low-oxygen region now spans over 6,000 square miles each summer — an area roughly the size of Hawaii.

Long-term studies reveal that even when fertilization stops, ecosystems can take over a century to recover. At England’s Park Grass Experiment, where scientists have applied fertilizer since 1858, biodiversity has never fully returned.

Coral Reefs and Coastal Collapse

PC: Raphael Riston-Williams

Marine biologist Annelise Hagan sees the same imbalance in tropical waters:

With nutrient enrichment, macroalgae outcompete the corals. They take over every bare surface so coral larvae can’t settle — and once that happens, it’s very hard to go back.

Add overfishing, which removes the herbivorous fish that normally keep algae in check, and coral reefs shift permanently to algae-dominated wastelands.

Humans as a Planetary Force

We’ve now become one of Earth’s largest nutrient sources. The nitrogen we create through fertilizers and fossil fuel combustion rivals all natural processes combined. Every raindrop now carries traces of human chemistry.

This isn’t just about agriculture — it’s about our relationship to natural cycles. Ecosystems thrive through feedback loops: nutrients recycled, energy shared, waste absorbed. When we break those loops, we don’t just harm nature, we undermine our own resilience.

Regeneration from Soil to Sea

The solution isn’t simply “less fertilizer.” It’s smarter systems that mimic the nutrient cycles nature already perfected:

- Regenerative agriculture that rebuilds soil microbiology and organic matter

- Wetlands and riparian buffers that trap and transform runoff

- Cover crops that hold nitrogen in the ground

- Bioreactors and algal systems that recycle waste into new resources

With Cultivating Currents’ Living Loop Lab (L³), we’re mapping these connections in real time. From the Great Lakes to the Gulf, we, along with our citizen scientists, will collect water samples, measure nutrients, and document how what happens on land flows downstream into our shared waters.

Why This Matters

Nutrient pollution sits at the heart of multiple global crises, biodiversity loss, climate disruption, and food insecurity, yet it’s also one of the most solvable. When we start to see the planet not as separate systems — soil, rivers, oceans — but as one living loop, we can begin to restore the cycles that sustain us all.

As Harpole puts it:

When we add too much nitrogen, the system becomes simple — and simple systems are fragile.

Regeneration is about bringing back complexity — in our fields, in our waters, and in the way we think about the world around us.